Quote in Los Angeles Times

Enzo Yaksic, who runs the Atypical Homicide Research Group, said serial killers are enamored of the ability to control a community, and also hope to garner sympathies from those who might admire or commiserate with them. Yaksic said it is unclear how much sooner Eric Rudolph could’ve been caught in a digital world. “Advances in technology have altered the landscape of multiple-murder as the decline in serial homicide since the 1990s directly parallels the near ubiquity of surveillance technology, cellular phone and Internet use,” Yaksic wrote in an email. “Law enforcement’s ease of tapping into cellular phone tracking records, their callback of Internet search histories and receipt of surveillance videos have greatly aided many modern day investigations by providing the whereabouts of potential suspects and the outlines of future plans.”

Quote in The Washington Post

Enzo Yaksic, a criminal profiler and founder of the Atypical Homicide Research Group in Boston, said serial killers are generally motivated by a desire for revenge — “angry and resentful individuals who believe they are settling a grievance for perceived or actual wrongs and blame others and the systems they represent for their problems.” The suspect in the Phoenix-area killings fits that description, Yaksic hypothesized based on information published about the deaths. “This offender espoused the methodical calculation of the serial killer, the vengeful nature of the mass murderer and the swiftness and exigency of the spree killer,” Yaksic said. “Few offenders are adept at cycling from one typology to the next in quick succession, as was done here.” There have been several serial killers in the Phoenix area over the years, said Yaksic, whose organization maintains a database on 2,700 serial killers nationwide.

Quote in The Boston Globe

Enzo Yaksic, founder of the Atypical Homicide Research Group, who has followed Sampson’s case since his arrest, said Sampson’s lawyers will want to try to keep him from becoming combative or indirectly blaming his victims, and so a prepared statement may be more proper. Yaksic questioned whether Sampson could ever seem genuine before a jury, considering the brutality of his crimes, though he cited the ability of some serial killers to “feign remorse.”

Quote in Associated Press News

Enzo Yaksic, director of the Atypical Homicide Research Group, said Little’s wandering lifestyle appears to set him apart from the habits of American serial killers such as Gary Ridgway, the so-called Green River Killer. “Little is unique in that modern day serial murderers rarely travel the distances he claims to have traversed and instead select vulnerable victims from their own communities,” Yaksic said. “This behavior, paired with his selection of vulnerable people, no doubt contributed to his longevity. Most serial killers in today’s society kill two or three victims and are caught within a few years.”

Quote in ABC News

"The tactic of having a serial killer draw composites of his own victims is unprecedented," said Enzo Yaksic, a crime researcher who helped build the first national serial killer database. "This goes to show how serial killers retain minute details of their crimes and mull them over years later as these are the conquests that made them feel powerful and in control." Little, he added, could "inflict trauma on his victim's relatives indirectly with the drawings and that is undoubtedly a small payoff for him."

Quote in the Toronto Sun

To learn more about these mind-boggling crimes, we turned to Enzo Yaksic, director of the Atypical Homicide Research Group. The AHRG is an active network of 150 researchers, law enforcement professionals and practitioners organized to address the societal issue of serial and mass homicide. Yaksic is a data wrangler who has studied criminal behaviour most of his adult life. He is changing the work done on serial killers through his knowledge and his capacity for teamwork — creating a massive database by convincing all manner of experts in the field to pool their research and then work together. Yaksic’s work covers everything from contributing to the arrest of criminals to advising on true crime shows such as The Killing Season. We asked him for input on the McArthur case in Toronto.

What do you think about the criticism aimed at our police?

“While some might claim that police ignored these victims because of their sexual orientation or marginal status, the secrecy was more than likely a deliberate tactic designed to ensnare McArthur by allowing him to act as if no one was watching him. The existence of Project Prism and Project Houston is evidence that police learned from the repercussions of the (Robert) Pickton case and certainly lends credence to the idea that they took the presumed deaths of Selim Esen and Andrew Kinsman and the disappearances of Skandaraj Navaratnam, Abdulbasir Faizi, and Majeed Kayhan and others seriously.”

People are surprised to hear that the number of serial killers is actually declining. Can you address that?

“Better law enforcement, newer technology, ever-present surveillance equipment, an educated public and the vigilance of potential victims have all contributed to increasing the odds that a serial killer will be apprehended before they can amass larger victim counts and making it more difficult to commit their crimes.Because not all offenders enjoy the act of killing others, many would-be and wannabe serial killers have begun to sublimate their desires into other outlets such as complacent sexual relationships and violent pornography.”

Any insights into an alleged killer like McArthur?

“Most will assume that McArthur’s alleged crimes span many more years than just the latest spate of missing persons cases but it can take decades for some serial killers to convince themselves of what they are at their core and that the conditions are right to begin their campaigns. There is an internal wavering that can occur as these killers struggle with their thoughts and feelings towards others and question whether or not they have the capabilities to kill serially.”

And what about motive?

“It is too early to tell if McArthur gained any satisfaction or psychological gratification from the demise of his alleged victims or if they were killed as merely a utilitarian need to eliminate a living witness…Some serial murderers loathe themselves so deeply that they assume others view them in the same way, a type of confirmation bias more prevalent among gay serial killers and one that can incite high levels of rage.”

What should people know about crimes like this?

“All serial murderers are unique and the similarities or differences will become apparent once more information is released by law enforcement…In the past, offenders have eluded capture for a multitude of reasons, usually due to circumstances beyond their control and a hefty amount of luck rather than their own cunning skills or the types of victims they target. Discrepancies in how researchers have defined serial murder have led many to believe that these offenders only victimize strangers purely for sexual reasons, giving romantic suitors, partners and acquaintances an unfortunate false sense of security. Serial murderers have historically capitalized on misinformation like this and taken intentional advantage of the willingness of others to trust one another.”

Quote in Cleveland.com

Serial murderers often prey upon those leading high risk lifestyles, said Enzo Yaksic, who also works with MAP and has researched serial killing for more than a decade, helping to build the first serial homicide offender database. Such offenders count on victims "not being missed." The offender in at least some of the Cleveland cases likely "lives, works and prays in the same community from which he selects his victims," Yaksic said.

Quote in US News & World Report

"Successful serial murderers are determined, adaptable and cognizant of their surroundings, which allows them to learn from their mistakes, improve their abilities and implement new tactics to remain steps ahead of those searching for them," said Enzo Yaksic, director of the Atypical Homicide Research Group.

Quote in NorthJersey.com

While prosecutors never used the term, the slayings fit the pattern of a serial killer, said Enzo Yaksic of the Atypical Homicide Research Group, a think tank that studies serial murder suspects. Wheeler-Weaver followed a methodical and obsessive pattern, choosing victims of the same race, employing the same killing method and looking to hide or destroy bodies. He also shared another common trait with serial killers, Yaksic said: an interest in law enforcement.

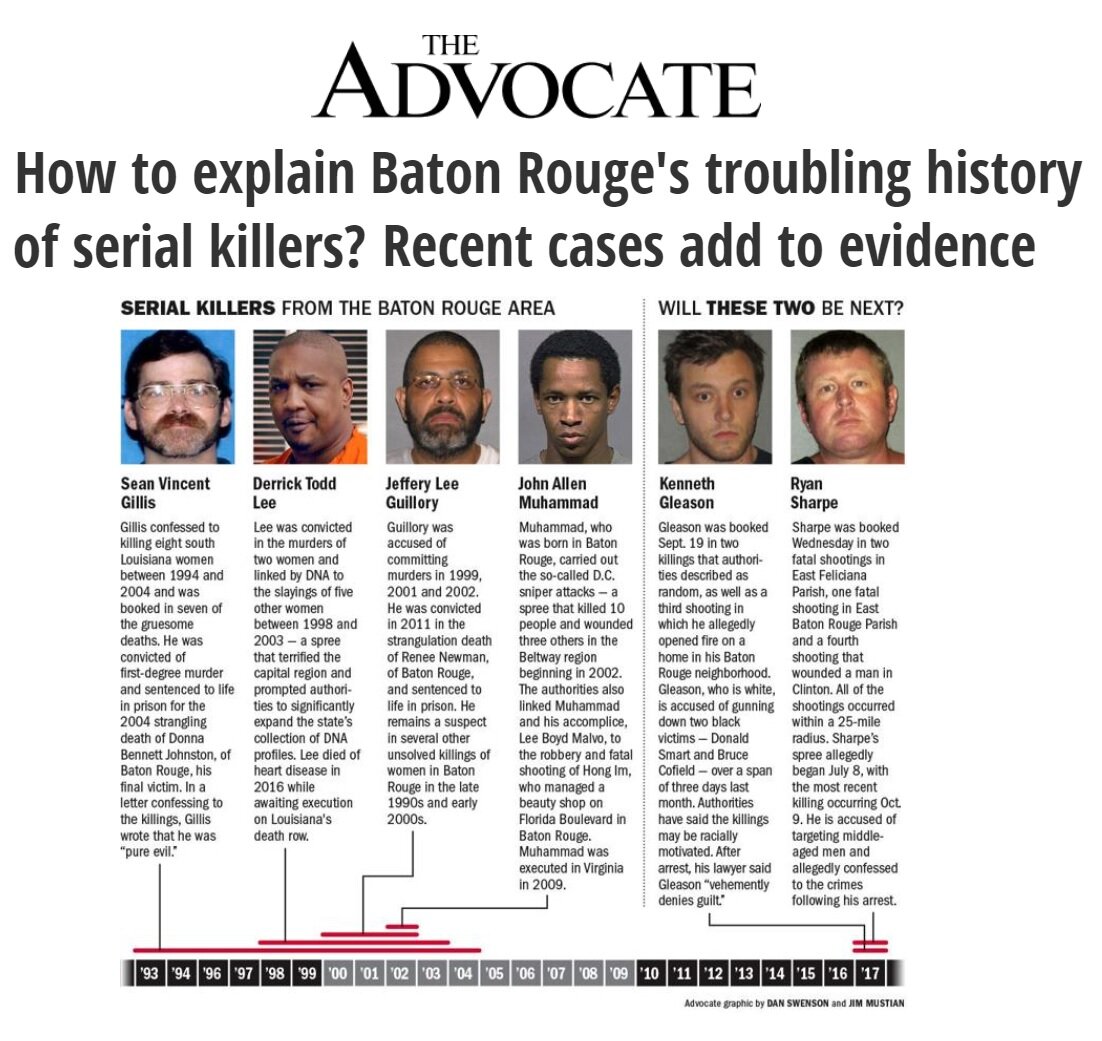

Quote in The Advocate

The Atypical Homicide Research Group said last week that Sharpe fit the profile of a serial killer in part because he used a firearm — the weapon most commonly chosen by such offenders — and allegedly confessed to authorities. But the case is unusual in that Sharpe is accused of targeting men "in the late stage of their lives," said Enzo Yaksic, the group's founder and a longtime researcher of serial killers. Yaksic also said it is "exceedingly rare for serial murderers to be motivated to kill by mental illness or by urges beyond their control." "More often than not," he wrote in an email, "serial killers deliberately choose their course of action and can also decide to end their campaigns of violence on their own terms. While some serial killers operate at the behest of a desire to placate an internal drive for gratification, it is a myth that all serial killers are compelled to kill."

Quote in AL.com

That was enough to pique the interest of Enzo Yaksic, head of the Atypical Homicide Research Group (AHRG) at Northeastern University's School of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Yaksic said his research leads him to think that the serial-killer phenomenon is over-hyped in popular culture, and that so far this case looks more like a wannabe than a second coming of Gacy. "I would say that given the victimology, there's no direct threat to the community," he said. Most kill two victims before being caught, said Yaksic. He referred to those who kill five or more as "prolific," and he said they're rare. In fact, he said, he thinks they are growing more rare over time. "It hasn't been a very popular theory," he said. But "It's actually stunningly obvious, especially now in the information age." Yaksic said that in the '80s, study of serial killers focused on a relatively small number of cases, such as Gacy and Ted Bundy, and that might have resulted in a somewhat oversimplified understanding. Fictional characters such as Hannibal Lecter and Showtime's "Dexter" embellished that to create some templates: Serial killers are weird, lonely, frustrated losers, or amoral, psychopathic masterminds, or a little bit of both. In reality, Yaksic said, things are more complicated. If someone with the potential to become a full-fledged serial killer gets caught after his first killing, what does that make him - a serial killer whose body count stopped at one? And where do you draw the line between a serial killer who hasn't gotten started yet, and a wannabe who's never going to be? "Our field, until recently, has never been a data-driven field," Yaksic said. It's been shaped by anecdotal case studies. And wannabes are "even further removed" from a solid understanding. One reason "why the wannabes are not studied ... their competency is in question," he said. Meanwhile, Yaksic said, the world itself is becoming more data-driven. The ubiquity of cell phones makes it easier to track people. Social media might give a killer new ways to lure a victim, but it also makes it harder for people to simply disappear. Connectivity in general makes it easier for authorities to spot a pattern of killings spread across multiple jurisdictions. Classic serial killers remain among the most difficult cases to crack, Yaksic said, in part because they target strangers. But in some ways the risks have gone up, and "offenders definitely calculate the risk involved." He said that if the risk of getting caught is high enough, a potential serial killer might simply seek other forms of release. He said he thinks some find relief through intense role-playing - something perhaps comparable to a specialized sexual fetish. "Many of them don't actually need to kill in order to get what they want, which is gratification," Yaksic said. Yaksic's theories aren't all new, by any means. The FBI published a "Serial Murder" handbook in 2008. Its introduction says: "Serial murder is a relatively rare event, estimated to comprise less than one percent of all murders committed in any given year. However, there is a macabre interest in the topic that far exceeds its scope and has generated countless articles, books, and movies." After referencing Jack the Ripper, the Green River Killer, Ted Bundy and "Silence of the Lambs," it says that "much of the general public's knowledge concerning serial murder is a product of Hollywood productions." To that, Yaksic adds a modern refinement: Podcasts catering to the popular interest in real or purported serial killers. "Some of these individuals are directly responsible for promulgating the myths," he said. Still, much remains unknown, both in the Sebastian case and in the larger matter of serial killings. Sebastian could turn out to have a darker past than anyone has yet realized, though Yaksic said he finds it unlikely. The unknown allows for speculation, and it allows for doubt. It allows for the possibility that serial killers are out there, hidden in the "dark figures" of unreported crime. Yaksic doubts it, but it remains a difficult argument to kill. "It's impossible to prove," he said.

Quote in The West Australian

Perth may not have encountered evil like Jemma Lilley, who was last week convicted of the murder of Aaron Pajich-Sweetman, for many years. But researcher Enzo Yaksic, who runs the Atypical Homicide Research Group in Boston in the US has seen it all too often. And he says Lilley fits the mould of a “killer interrupted”. “In an age where modern society is saturated with entertainment glorifying the serial murderer it is no surprise that young minds will attempt to emulate what they consume,” Mr Yaksic told The West Australian. “This obsession clouds their judgment as they base their dreams on fictional offenders endowed with special abilities and powers which ensures that any semblance of their own self-preservation is overlooked as they assume they can carry out their crimes in the same manner as their idols. “Surrounding oneself with such objects aids in the eventual morphing of what was once a passive idea into homicidal ideation, daily intrusive thoughts so all-consuming that action becomes a foregone conclusion,” he said. Lilley, 26, has been added to the growing list of thwarted serial killers. Mr Yaksic has developed what it is believed to be the most comprehensive non-government database of killers in the world. Comparing Lilley with others in his database, Mr Yaksic sees many similarities. “Serial killer wannabes typically display the intent to cause harm to others early on in their lives and spend an inordinate amount of time entrenched in the ethos of what they believe it means to be a serial killer,” Mr Yaksic said. “Above all else, serial killer wannabes yearn to assume the control of their own narrative but sometimes require the assistance of others to realise their goals.” “While partnerships are rare among serial homicide offenders, when pairings do form they generally conform to the submissive/dominant archetype but not always on the basis of age differences,” Mr Yaksic said. “Relationships of this nature are usually enveloped by the shared sense of responsibility to the proposed criminal act and are less about the camaraderie provided by pro-social friendships.” Lilley’s reliance on Lenon ultimately led to the downfall of both. Mr Yaksic said that while it seems a small but significant group of people follow through on their killer fantasies, very few ever become what they aspired to be. “Lilley joins the ranks of several other would-be or wannabe serial murderers whose careers were interrupted by any number of factors — ill-conceived plans leading to a failure to follow through, ineptness, immature grasp of consequences and missteps that raise suspicion of witnesses,” he said. “Increased pressure from law enforcement and better technology, like ever-present cell phones and surveillance equipment, also forces serial killers to behave in ways not typical to how they operated in the past.” And despite the continuing fascination with those who kill, and want to kill again, Mr Yaksic says they are still extremely rare. “Tracking instances of serial homicide over the past few decades has revealed that there are far more fans of serial killers and wannabes than actual offenders from year to year,” he says.

Quote in Associated Press News

"The contents of Christensen's internet search history demonstrate his lack of knowledge of basic things that proficient serial killers with high body counts would know," says Enzo Yaksic, a Boston-based researcher who has studied serial killers for over 15 years. But Christensen does share some traits with convicted serial killers. He targeted a stranger, say prosecutors. Sexual fantasies underpinned his desire to kill and he idolized serial killers in history, especially Ted Bundy. A recent study co-authored by Yaksic noted serial killers often share a fondness for violent fictional characters. Christensen's favorite novel, prosecutors say, was "American Psycho," about a young professional who kills at night. Choking is also a marker for some serial killers, said Yaksic, because it satisfies their craving for control. Actual serial killers, explained Yaksic, demonstrated more patience than Christensen, who only happened upon Zhang and pulled up to her during the day along streets lined with surveillance cameras. Yaksic says he thinks there's only "a minuscule chance" Christensen killed before, categorizing him as "wannabe serial killer." "Wannabes," he said, "are often compelled by a mixture of emotions and hubris ... aspects of their personality that lead to their apprehension before they come close to achieving their goals."

Quote in Fort Worth Star-Telegram

Enzo Yaksic, co-founder of the Atypical Homicide Research Group, which specializes in using data to understand serial homicide offenders, said that according to the group’s data, 2 percent of serial murderers target the elderly. “Of those offenders, 63 percent committed a home invasion against the elderly for the purposes of obtaining items through burglary,” he said. “Chemirmir fits the serial killer profile in that he enacted a ruse of posing as a caregiver specifically to place himself in a better position to take advantage of the elderly, a vulnerable population that often live alone and are not always closely monitored.” Yaksic said that serial killers most often con potential victims into the belief that they’re good people in order to gain closer access to them. As law enforcement and local medical examiners dig through about 750 elderly deaths in an attempt to find more possible victims, Yaksic thinks there are more. “The scope of Chemirmir’s crimes is probably vast since he became adept at breaking into residences undetected or appearing to belong there to perform maintenance knowing that he would be overlooked,” Yaksic said.

Quote in The Greenville News

Experts told The Greenville News that it is highly unusual for a serial killer to begin with a mass murder. Enzo Yaksic, who runs the Atypical Homicide Research Group and has built a database on serial killers for use by law enforcement, described that pattern as "incredibly uncommon.” “These offenders remain undetected for large expanses of time due to a mixture of diligence on their part, a carefully constructed façade, the types of victims that they select and lucky breaks,” said Yaksic, who served as a technical consultant for the upcoming A&E show, “The Killing Season.” “Most serial killers are or have been married, frequently have arrest records and are often forthcoming upon capture, either out of pride or relief that their campaign can end,” Yaksic said. Yaksic said many of the behaviors at the root of serial killers emerge when they are young, though they sometimes go undetected. “His parents understood Todd to have a great deal of anger, but the full breath of what he is capable of cannot be known until much later in life when his behavior is not consistently monitored by others,” Yaksic said.

Quote in Tampa Bay Times

Enzo Yaksic, who runs the Serial Homicide Expertise and Information Sharing Collaborative, is not a professional criminologist but an expert with a database of thousands of murderers that he uses to develop profiles of serial killers. He doesn't try to get inside their minds; he tries to bring science to the art. He shared his profile of the Seminole Heights killer with the Tampa Bay Times. The murderer seems to ambush victims, coming on them suddenly with a gun. Most serial killers are men, so this one probably is, too. He may be traveling by foot or bicycle, moving quietly. The mode of transportation suggests a younger person, 21 to 35. The killer probably has a "deep and personal relationship with the area," Yaksic wrote. "The disparity between the offender's perceived lower status may be driving his motivations to victimize those from other statuses," Yaksic wrote. Since at least two of the killings happened later in the day or at night, the "timing could indicate that the offender is employed during the daylight hours in some menial capacity based on his potential age range." Though predicting race is difficult, Yaksic wrote that in such a diverse area, the killer is likely from a minority group. He doubts the murderer is mentally ill but probably enjoys outsmarting law enforcement officers. In an interview, Yaksic said the Seminole Heights killer seems to match a pattern he has seen in recent years — younger, spree-like serial murderers who are more motivated by anger than sexual desire. It's possible the killings could even be gang activity or an initiation ritual. "The newer version of the offender is the run-and-guns," Yaksic said. "They don't take any kind of gratification from spending time with the body." Everyone can watch profiling with TV shows like Criminal Minds and Mindhunter, but it remains a tricky, evolving process. Yaksic said many might refrain from sharing their profiles, for fear of being wrong, but he trusts his data. And there will always be outliers.

Quote in Pensacola News Journal

Enzo Yaksic is a homicide researcher who took a particular interest in Boyette and Rice’s alleged crime spree after the first two attacks. Yaksic helped found the Atypical Homicide Research Group, and aids in compiling a database on serial and spree killing attacks in an attempt to understand what triggers horrific crimes. Boyette exemplifies a new subgroup of killer that’s become prevalent since an unexplained decline in serial killers around the 1980s. The spree-serial hybrid is a dangerous mix of the cold, calculated attacks of a serial killer and the emotive unpredictability of a spree killer, Yaksic says. Rice’s involvement is what sets the circumstances even farther apart from the norm, and whether she was coerced into her actions or she was a willing participant, Yaksic said the unmatched possibility for advancement in understanding team killing was lost when Boyette took his own life in that motel room. “It’s rare for a woman to be a serial killer in and of itself, but to team up with a male, it’s very rare,” Yaksic said. “Typically when those pairings occur, it’s based on a common ideology. Without the other, they wouldn’t be committing these crimes." Based on the details that have so far been released regarding the events, Yaksic said, it’s possible Rice had been groomed to be a submissive accomplice for some time by a man who had an established ability to both commit crime and get away with it. But, he also can't rule out the possibility she’s just as guilty as Boyette. And while police may have initially feared for Rice's safety, Yaksic said, there must have been some kind of established connection between the pair that was evident to police to prompt them to change their view of Rice from victim to accomplice. “I honestly thought he was going to kill her, too (in the motel room). The fact she was allowed to leave, that could hint there was some kind of deeper connection there,” Yaksic said. “It’s almost as if he claimed her already as dead because she doesn’t have any recourse, there’s nothing she can say that will really prove her innocence. She’s alongside him for the entirety of the events.” “Unfortunately he’s dead, so we can’t know what his planning was, but I’d like to bet he had this homicidal ideation for quite a while and it just manifested itself when it did,” Yaksic said. “Historically and especially with spree killers, they’re in such a frenzy that they don’t even plan on their escape, they know it’s going to come down to their capture,” Yaksic said. “I think they even knew that when they were buying the ammunition, that they would need to use that eventually.” Researchers are calling for more in-depth study of the factors that trigger or lead into multiple homicides. Too often law enforcement and criminal profilers are focused on how best to apprehend the killer that they ignore any study into what genetic or environmental factors mold that type of person in the first place, Yaksic said. Researchers have shied away from referencing the homicidal triad, a series of risk factors known as bedwetting, animal cruelty and fire-setting that are often seen in children who become killers. The legal system’s overwhelming intention to protect juveniles who commit crimes means that even if a child kills an animal at 15 and graduates to homicide at 18, that prior crime often isn’t taken into account, Yaksic said. Plea deals and agreements can hurt research like Yaksic's, he said, as academics only include the offenses for which someone is sentenced, which can provide a sometimes incomplete view of their background. It’s likely he was building up the confidence to kill over an entire lifetime of assault charges, Yaksic said, and now that he’s dead, the public may never know the entire story behind his killing spree except for the version told through Rice.

Quote in USA Today

Enzo Yaksic, founder of the Serial Homicide Expertise and Information Sharing Collaborative, said Vail's arrest marks the oldest of a serial killer suspect in the nation's history.

Quote in Clarion Ledger

I [Jerry Mitchell] shared information from Frenzel’s visits with the expert, Yaksic. He provided many hours of advice and insights, saying Vail seemed “more in line with a cult leader” than a suspected serial killer.

Quote in USA Today

"Glee would have killed again if given the chance and most likely intended to acquire additional victims," said Enzo Yaksic, a renowned serial killer scholar and founder of the Boston-based Atypical Homicide Research Group. Enzo Yaksic, founder of the Boston-based Atypical Homicide Research Group, a collaborative network of researchers, law enforcement and mental health professionals that collects and shares data on serial killers. Yaksic said Glee demonstrated many of the same behaviors of serial killers, including binding his victims and letting at least one of them die slowly by asphyxiation. "That his assaults occurred over three decades and his victims were usually female shows that Glee’s hatred toward women, a hallmark of serial homicide, manifested gradually until it culminated in the deaths of Salau and Sims — two women who refused to comply with his demands," he said. Yaksic said throughout life, Glee appeared hyper-focused on securing sex partners. When Salau resisted, he resorted to kidnapping and rape. “It could very well be that her resistance to his advances is what triggered him to respond with violence,” he said. “His second victim was collateral damage given that she had information linking him to the first homicide.” Yaksic said it’s unlikely Glee killed before given the missteps that led to his capture. He didn’t have a vehicle or viable escape plan and picked a victim in Sims who could be linked to him easily. He also left behind a wealth of evidence at the scene. “Serial murderers spend an immense amount of time in a state of what we call homicidal ideation or fantasy,” Yaksic said. “It can take a number of years to work up the courage to kill and even longer to convince themselves they can escape apprehension.” Yaksic added, “They can be lazy and take the easiest pathway to murder. The tension that builds in them becomes all consuming and is sometimes released at the first opportunity.” Yaksic said two-victim serial killers are just as dangerous as those with higher death counts, though they're often ignored by scholars. He said it's important for researchers to study them and the public to be aware of them. "Discounting them and not studying their behavior patterns may lead to opportunities for future two-victim killers to accrue more victims," he said. "The Glee case is evidence of how vitally important it is for potential victims of serial killers to remain vigilant."

Quote in NorthJersey.com

"Den Hollander exhibited characteristics of many serial killers from the past, mainly the appearance of being unstable all the while furtively calculating the next steps towards using violence as an equalizer," said Enzo Yaksic, director of the Atypical Homicide Research Group, a network of more than 100 academic researchers, law enforcement professionals and mental health practitioners working toward a greater understanding of atypical homicide. "I am convinced that Den Hollander would have killed the future targets he identified on his hit list if given the chance." Yaksic, of Boston, has spent the past 15 years studying serial murderers. He has overseen and collaborated on several studies on the topic, published numerous peer-reviewed articles researching serial killers and is working on a book dealing with data relating to serial killers. "Outwardly, Den Hollander’s life may have appeared to be a success with all the media interviews and exposure," Yaksic said. "But privately, Den Hollander was a financial failure with no social support network." Yaksic said serial killers are known to "rely on this duality" to keep people guessing about their capabilities, what to expect from them, and whether or not they pose a threat. "Den Hollander will go down in the annals of criminology as a combination of a later-stage George Sodini, the man responsible for the LA Fitness shooting in 2009, and a less successful Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer," Yaksic said. "Den Hollander is just another dejected man who used the internet to share his discontent with anyone who would listen." Yaksic said the goal of a serial killer leaving records behind that detail the buildup to their killings "is a tactic meant to spur others into thinking they could have prevented such atrocities if they had only cared enough to reach out and befriend them." "Most often, though, these types of offenders are too far gone as their thought patterns have been reinforced through years of viewing their lives through a lens of self-pity," he added. He said Den Hollander acted in desperation with his first marriage, "which only served to solidify his belief that women were evil beings bent on causing men pain." "In actuality, Den Hollander caused himself to be labeled as an outcast given his viewpoints went consistently against the grain," Yaksic said. "Den Hollander is the prototypical externalizer; he was never to blame for any of his own shortcomings. Serial killers are notorious for lacking the ability to take blame or introspect." Den Hollander also claimed in an online screed to have had the seeds planted for his campaign against women in childhood by his own mother, "a typical refrain heard from many serial killers," Yaksic said. Yaksic said Den Hollander possessed one of the main common links of serial killers: a disdain for humans. "What makes serial, spree, and mass murderers unique from one another is the method they use to spread their hatred to others," Yaksic said. "The usual motivation for killing serially is the offender’s desire to reestablish control and to quell feelings of powerlessness. These killers will murder across genders as their grander goal is using homicide as a means to communicate their feelings of ill will to the world." He said Den Hollander’s use of the what authorities believe was the same firearm in both cases is a "type of consistency in forethought often found in serial homicides." "It is a myth that serial murderers only kill strangers," Yaksic said. "Serial killers have been known to target acquaintances when they resolve to use murder as a means to settle a conflict." Yaksic said it's interesting Den Hollander’s hatred, while aimed at women, was taken out on men. "That goes to show that victim preference matters little to someone that aims to sow discontent and share their misery with others," he said. Yaksic also said Den Hollander was unique in that he initially sought to "smite" his enemies in the court system. "However, once that approach began to fail, he reverted to the tendencies innate to him, those that made him a serial killer," he said.